Morning

Hotel to Surgery Center and Pre-Op

25.04.2024 - 25.04.2024 71 °F

The 4:15am alarm is, simultaneously, dreaded and welcomed.

Various morning duties are completed, ride the elevator which is adorned with the slogan "Le non e vero e ben trovato" which I take to mean "It is not true if it is not found," which I fail to comprehend. We check out of the hotel, chat with an Uber driver while we wait for the valet to retrieve our car and then make our way through somewhat poorly written directions to the hospital parking facility. All the parking spaces near the entry door are reserved for physicians—a feature whose advisability I question given that this is the place where everyone else is mobility impaired and must gain egress.

The door through which we are to enter is locked and there is no intercom. Fortunately, nurse Floyd appears and lets us tailgate him into the building. Down the scrubbed hallways at three minutes before 6:00am, our designated arrival time, we finally locate the waiting room where a crowd has gathered ahead of us.

There are 19 seats and all but two are filled. We claim them. HGTV plays a bit too loudly on a wall-mounted flat screen but is muted by the hum of a combination snack and beverage machine.

6:15am comes and goes.

There are two women seeing to all these patients and their accompanying escorts and family members. Soon, five more people are standing. One man—husband to a patient—seems unaware that he is talking too loudly about how much he likes Good N’ Plenty candy and that the boxes now are too big. He describes what is happening to his wife—already taken through the gateway doors to whatever is next—to the rest of his group which is too large for this room. Two people doze, one helps another whose first language is Spanish rather than the English on the form through which he struggles while two more wear covid masks while eyeing the rest of us suspiciously.

6:30am comes and goes.

Beryl occupies herself with her trusty machine, an iPhone 14, reading daily newsletters from Heather Cox Richardson and Joyce Vance and scanning this news site and that news site to pass the time. She and I, along with more than half of those here gathered are dressed in all black. It occurs to me that should not be taken as a negative sign.

6:45am comes and goes.

Other than the loud man’s spouse, nobody seems to be making their way from this staging area to whatever is next. The two attendants are most often missing, presumably occupied with intake processing steps being taken outside our view. If pre-surgery anxiety management is a priority here, process improvements are called for.

Ms. Perez is called for. She is dressed as one might imagine a Peruvian woman to be. Then Zachary is called. He and his escort depart us. One of the attendants enters the room and counts how many of us remain. If my count and hers align, the number is fourteen.

A man whose name I missed is called. He leaves alone. It was made clear to us that each patient must be accompanied when it is time to leave but I don’t recall any requirement that patients could not be unaccompanied when they arrived. I feel sorry for him at that moment. Having a hand to hold at this time would be welcome.

Beryl is oblivious to all of this as she remains focused on her device. The loud man tells his companion how he can do most of the therapy he is required to take at home. Fortunately for him he has access to a pool to complete the zero gravity portions of his routine. His companion opts to describe how her friends knee replacement was loose and she fell and there is something causing pain and she can’t do anything. I want to take her aside to advise that she either lower her voice or change the subject but she, “Ginny,” is called back before I must decide to intervene. Unfortunately, Ginny is replacing another woman who had been with the loud man’s wife who returns to join those of us waiting.

“Rubenstein?” One of the dozing patients and his escort are called back. The number of empty chairs is growing.

7:00am makes its entrance as the rising sun brightens our view through the window of our waiting chamber. Ms. Gamble is called and the door slams behind her. The loud man speaks of his kneecap and how it impacts his biking as the first of the 7:00am appointment wave begins to enter the waiting room.

An arriving family of three includes a toddler in a stroller. He is fussy. His goateed/tattooed dad wears an “Eat, Sleep, Roar, Repeat” t-shirt beneath his Jacksonville Jaguars ballcap while his mother prepares an iPad to distract him. They can’t find the proper WIFI connection, and the small boy begins to lose his patience. I resent the dad because he thought to bring a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee along with him this morning and I did not. The iPad, thankfully, works and, amazingly, the boy finds it interesting even without audio.

The loud man begins to pace, replacing his speaking with the squeaking of his crocs on the laminate wood floor. HGTV, earlier lost to my ears, worms its way back in as still another new patient arrives.

Were it not for the opportunity to distract myself by this journaling of these events I would, by now, begin a path toward rage.

7:15am. She is called back.

We go to Room Six. Dr. Summers is looking in the room for her, but she isn’t there yet. If he is disappointed by that fact, he doesn’t let it show. Nurse Debbie takes vitals. BP is 127/82; excellent. Temp 36.5 (97.7 F) and pulse is 85. B signs a blood transfusion authorization form.

Debbie gives our girl a packed on body wipes with instructions to sterilize herself everywhere below her neck but not her “private” parts. She is given a toothbrush and mouthwash combination and given instructions for use of it. Into the bathroom she goes to disrobe, clean herself, don her surgical gown and return to me.

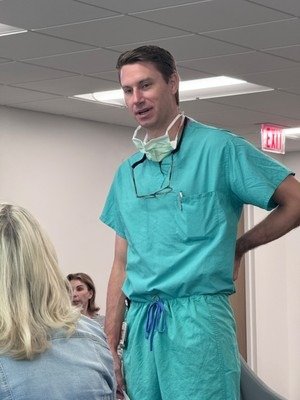

7:36. Dr. Summers appears with greetings and marks—and initials—her left hip. Debbie puts on an SCD device on her right leg to prevent clotting.

From the nurses’ station, I hear a nurse say, “20 more pre-ops” and another answer with, “we’re half way through.”

Nurses Jael and Mabel come in but see that they are way too early and after a quick introduction, they leave.

RN Madison arrives at 7:48 to draw blood. She had a friend named Beryl in Houston when, as young girls, they played soccer together.

7:55: Lactated Ringer’s IV hooked up.

ID bands go on both wrists. On the right, an ID band and blood ID band. On the left, a “fall risk” band which all anesthesia patients receive and a pollen allergy band.

8:00: Dr. Patrick Johnson, anesthesiologist arrives. He wears a Buffalo Bills surgical cap and winces when he learns of our Kansas City connection. He will deliver propofol and a shot in her back and a 3-day pain shot in her hip. Our interaction with him is finished five minutes later.

Pre-op meds of Tylenol, Flomax, Pepcid, Zofran and Lyrica are either taken orally or inserted into her IV line. There is lots and lots and lots of paperwork and several signatures. She is asked countless times her name and birthdate and why she’s here. They take no chances.

Mabel is back but, this time, with Marcello who identifies himself as the nurse anesthetist. That’s at 8:22. Three minutes later, they roll her away from me. We exchange kisses and “I love you’s” and I make my way back to the waiting room for what I am told will be a two-hour wait.

The place is busier than usual today, I overhear. They will perform 50 cases today. Their normal workload on a Thursday is only 30. Summers is doing 5 or 6 of those. He uses two operating rooms in sequence; we are his second case of the day.

The waiting room is jammed. I snag a chair and small round table in the back corner with a great view of HGTV. The loud man, now called “Steve” and now wearing sunglasses, holds court about this and that as his companion tries to answer her mobile phone—much too loudly repeating, “Hello, hello, hello.”