Chapter Eighteen: Kigali To Volcanoes National Park

First, the Genocide Museum

12.14.2021 - 12.14.2021 80 °F

View Morocco + Uganda + Rwanda on paulej4's travel map.

Before I continue on telling my tale of gorillas, let me deal with something of vastly greater consequence. Most of you know that I am an activist for transgender rights. A dear friend of mine, an attorney who is a specialist on these things, wrote me overnight saying: "Hi Paul, I am thrilled that I can tell you late Friday evening we got a jury verdict in my case against Blue Springs School District involving access for transgender kids to the bathrooms and locker rooms consistent with their gender identity. The jury gave us a 12-0 decision for Plaintiff and what we think is the largest award of damages for a transgender Plaintiff in a discrimination case in U.S. history! I have never been so excited and exhausted at the same time! It only took us seven and a half years to get here! I hope you are enjoying Africa! Now that the trial is over I will have a chance to get caught up on your blogs!" That is a big deal if you are a trans kid or the parent of a trans kid. So I begin today by saying to Madeline Johnson Esquire: Bravo! I am excited that kids can finally be allowed to comfortably relieve themselves at school and not have to "hold it" for the entire day until they get home. Hats off to you Madeline. Hats off.

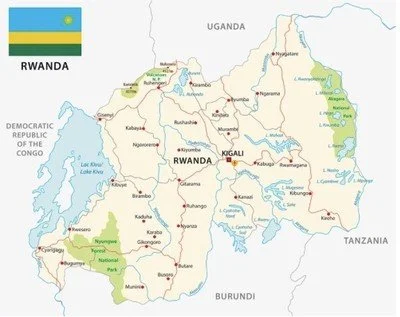

Today, I move from the city of Kigali to Volcanoes National Park which is In northwestern Rwanda and is a 62 square miles park, home to five of the eight volcanoes in the region: Karisimbi, Bisoke, Muhabura, Gahinga and Sabyinyo. Dian Fossey—inspired by Louis Leakey—did her amazing work here. Arriving in 1967, she is credited with saving the gorillas from extinction. In 1985, she was murdered by “unknown assailants” thought to be poachers, at her home. Perhaps you saw the 1988 film “Gorillas in the Mist” where Sigourney Weaver played her. Fossey wrote that here, “you shiver more than you sweat.”

Fossey was opposed to tourists like me—at least early on. It is said that once she saw how the money raised would help her achieve her goals, she may have moderated that viewpoint. Likely owing their very lives to Fossey, there are today 10 habituated gorilla groups in Volcanoes National Park.

The Kwitonda Group has 29 members including two silverbacks. The Hirwa Group has 18 members (including rare twins) and one silverback. The Agashya group has 21 members and one silverback who recently won control by ousting their former leader. The Umubano Group has 12 members and 4 silverbacks led by one of them named “Charles.” The Amahoro Group has 18 members and 4 silverbacks led by “Ubumwe” who is said to be calm and wise—which may account for the fact that he tolerates three other mature males. The Mafunzo Group has 12 members lead by one of the largest silverbacks in the park. The Sabyinyo Group has 16 members and 3 silverbacks, led by Guhonda who weighs in at 485 pounds. The Susa Group, the first studied by Fossey, has 18 members and 3 silverbacks. The Igisha Group boasts 25 members and four silverbacks. The Karisimbi Group is smaller with 10 members but with 5 of those being silverbacks. The Isimbi Group split from the Karisimbi and now has 16 members with but a single silverback. And, finally, the most recently formed Muhoza Group is the smallest of all with only 7 members and one silverback. It is said that the silverback Muhoza stole two adult females from the Hirwa Group in 2016. And so it goes.

It is the mountain gorillas of Volcanoes National Park that attract me and thousands of others to pay for permits to visit them in the hills. I have dreamed of this opportunity for many years. After two COVID-caused postponements, and after a successful stay in Uganda, I am finally in Rwanda. I learn after making my way here that friends Donna and Ward Katz have made this trip and consorted with the gorillas here. I'll ask around and see if anybody remembers them.

If you have not been following these chapters day after day, here is a word about our trekking guides. They are in contact with the same gorillas every day so they get to know them well—and vice versa. Guides try to stay between the small tourist groups in a way where the dominant silverback can see all the humans easily but is at least twenty feet away. We are told that if the silverback approaches very closely or—ahem, charges—it is very important that we do not move backwards, instead look downward adopting a submissive crouched posture. “If the gorillas stares at you,” we are told, “look down or away.” The rule is to never make sudden moves or loud noises. We are to never attempt to touch a gorilla and guides normally discourage young gorillas from touching us as that tends to irritate the silverbacks. Flash photography is forbidden. Each gorilla family can be visited only once per day for a maximum of one hour by a group capped at no more than eight tourists. Permits to participate are booked far in advance—up to a year-and-a-half—and when they’re gone, they’re gone. Things are different now with COVID causing cancellations galore resulting in a dearth of tourists like me.

There is no eating, drinking or smoking once we are within a distance of about two football fields from the family. No children under the age of 15 may participate in gorilla trekking. Our ubiquitous walking sticks must be left behind once we are near so that there is no mistaking them for weapons or threats.

Is it easy or hard to find the gorillas? That depends. Is it easy to flip a coin and get "heads?" Sure. But you might get "Tails" a few times before that happens. In Uganda, I had three very difficult treks and one easy one. I hear that Rwanda is typically easier terrain than Uganda but we shall see. The guide will have seen them the day before. Guides look for footprints, dung, chewed bamboo and celery stalks and abandoned nests from the previous evening. Maybe the family was as close as a half hour from camp; maybe four hours away. All of that trekking may be over steep, densely vegetated terrain at high altitude. It isn’t easy. If you’re sick, you can’t go—because you might not make it and because they don’t want the gorillas to catch whatever you’ve got. Sick, we are told, means not just COVID. It also means colds, coughs, diarrhea or flu.

I have the option to hire a porter to both carry my backpack for me and to help the local economy. One source says the minimum fee here is $10 per day but another says $20. (It was a minimum $15 per day in Uganda). Since my path is possibly through mud, stinging nettles and thick vines and over potentially steep and slippery trails, the choice, I learned in Uganda, is easy: hire a porter not matter--within reason--what the cost.

I am told that you can normally smell the gorillas before you see them but that wasn't the case last week. Upon approach, guides make soft smacking and groaning sounds to alert the gorillas that we are making a friendly approach. I’ll quote a bit here: “Sometimes, as a release of tension of as a display to the rest of the group, a male gorilla may charge and beat his chest, tearing up vegetation and hurling his tremendous frame directly at your tracking group. Despite the temptation to run, you must stand your ground, maintain a subordinate crouching position, and do your best not to flinch—for the gorilla will stop before actually reaching you and calmly return to his previous location, glancing back at you with smug satisfaction.” OK; sounds fun but it didn't happen last week. I kind of hope it does happen this week. Crazy? Well, yes, but you already know that about me.

But, what about today? Alarm at 7:00, breakfast at 8:00, Sam Elliot,

my driver/guide briefs me at 8:30 and we depart the Marriott at 9:00 in our Nissan safari vehicle. By the way, I got tons of smiles from Marriott staff this morning.

I learn that the site of this hotel was called the Garden Club before this structure was a reality and the scene of a military coup in 1973 when the head of the military surrounded the place when the President was holding a reception here. Before heading north, we stop at the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre. It is moving, infuriating, confounding and more other descriptors than i can muster. How can people do these things to each other? How? Clearly, Rwanda has a difficult past. Everyone hopes with a united Rwanda (nobody is a Hutu or a Tutsi--"we" are all Rwandans) this country can thrive.

We drive the city of Kigali. It is clean and modern--where I am anyway. Everybody wears a mask. Everybody. People speak English and Kinyarwanda, the native language. School begins with that language and switches to English with French as a subject (a few years ago, the language change was to French with English as a subject) My first observation is that Rwanda seemingly offers its citizens a much higher standard of living than does Uganda. My second observation is that they show it--at least some do--by smiling in public.

Traffic is sometimes chaotic.

Kinyarwanda: Murakoze is Thank You. Murakoze Chyane is Thank You Very Much. Mwaramuse is Good Morning; Mwiriwe is Good Afternoon. Almost nobody smokes. There is no litter. School is held in two shifts: morning and afternoon with teachers teaching both. There is a teacher shortage. One reason is that teachers, during the genocide were "of killer or killing age." Those who did the killing fled the country. There was nobody left to teach the children but that is slowly being remedied.

On the way to Virunga Lodge--about three and a half hours on mostly great roads, we pass the funeral of a very important person but we don't know who.

Every few miles there is an automatic traffic radar tower equipped with cameras. If you drive even a tad over the limit, you get an electronic ticket.

There are women with loads atop their heads, yellow phone/cash bank kiosks in every village and town. And there are smiles. Not from everyone, mind you, but from many.

Motorbikes (Motos) are taxis but here they are limited to the driver plus one passenger who must wear a helmet which is provided by the driver. In Uganda, there was no limit on passengers and no helmet law. Bicycles here "are not for sport, they are for business."

Upon arrival at the Lodge I am immediately greeting by Assistant Manager Alexis and he introduces me to my butler Leonard who presents me with a three tomato juice beverage. It is quite tasty. I am escorted to see the view--in the direction of sunrise--but a light sprinkle and heavy cloud cover modifies the beauty of what lies below: Lake Burera over which the sun rises.

From my Banda (named Kivu) I look West to Lake Ruhondo over which the sun sets. As you just discerned, the lodge is high atop a ridge with stunning views in all directions which will be even better when the weather is clear.

Leonard briefs me on my room, takes my dinner order, informs me that the three other guests are dining at 7:00 so I select the same time. I am told that I will receive a wakeup call at 5:00--coffee for me delivered to Kivu--and served breakfast at 5:30 so I am ready depart at 6:00 to see if the gorillas here remember Donna and Ward.

As I finish writing, lodge manager Emmanuel arrives and he chats with me for a while. As has been the case with each of the lodges, the staff is universally anxious to please. The other guests have arrived in the main lodge. I intend to introduce myself shortly. It is raining heavily outside.

I introduced: Fiona, Safi and Matthew from the U.K. Wonderful people.