Chapter 24: My Final Chance to Swim with Legal Persons?

Who's the oldest?

When one comes to Aitutaki, one should understand the situation. Whales here were recently recognized by treaty as legal persons. Cook Island indigenous leaders joined with their peers in New Zealand and Tahiti last month by signing a treaty that also pressures other national governments to join them. The personhood measure follows a similar 2017 New Zealand law that granted that status to the Whanganui River. So, certainly, the environment here is of a higher priority than some other places on our blue planet.

The river and whales hold high cultural importance to the Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand and this region. Māori people trace their ancestry to whales which contributed to their ancient system of navigation by leading them across vast oceans from island to island.

There is other whale protection here. The International Whaiing Commission has banned all commercial whaling within the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary which covers almost 20 million square miles surrounding Antarctica. Whales, being whales, tend to endanger themselves by crossing the sanctuary boundaries about which they are unaware at will.

Today was my final day to ring the doorbell of a whale and hope it not only answered but invited me inside for a visit. "You gotta see the baby," to quote a Seinfeld episode.

To beat the crowds of previous days, we agreed to meet an hour earlier--at 6:30am. Captain Onu and Tui agreed as did our Joshua Barton team. That meant skipping the lavish breakfast spread at the resort but, no, we wouldn't have to wade across the channel because the shuttle boat comes on line at 6:00 to facilitate the departure of day shift employees.

Josi, Olivia, Martin and I were at the ready when Manika and Josh pulled up in the raggedy Toyota van. Even at this early hour the roads were buzzing with motor scooters conveying locals from here to there. In many cases, many many maybe, the scooters strained under the weight of their operators. The Cook Islands rank second in obesity on an index published by the U.S. CIA World Factbook after Nauru. The top ten in this category are all near here followed by Kuwait in eleventh spot. The United States is number twelve. Josh told us of being in a store here where the shirt sizes ranged up to 12X.

We arrived at port, grabbed a coffee and muffin and boarded Bubbles such that we were on the water by 7:15. The temperature was unseasonably chilly and there was a strong breeze but, inexplicably, very calm seas.

Within a half hour we had come across our first spout. After a messy and uncharacteristically messy entry into the water, we had a hit. A mom and her calf rose up from an indecipherable depth, higher and higher, until these two majestic creatures were right below us.

This was the moment i had anticipated for months; the moment that I had thought would occur on Tuesday, on Wednesday, on Thursday but instead eluded me until this very good Friday. Having experienced an underwater fly-by in from sperm whales in Dominica earlier this year, I perhaps might have been jaded. But, no. These humpbacks are so different from sperm whales. Humpbacks have more striking coloring, enormous "wings" and a completely different profile. They move effortlessly. If they want to linger, they do. If they want to speed away--or down--they do. This pair was patient enough with us to split the difference and the time we shared, maybe a couple of minutes, was beautiful.

I am not the best of snorkelers. I am not the youngest and certainly not the most physically fit among those in the water with these creatures. I had to concentrate on the whales. I had to try to hold and aim my iPhone (in a waterproof case) without being able to see very well what the screen was showing me. I had to breathe.

These two photographs were taking by my fellow adventurers; that's me in both shots.

That was not our only encounter. The morning repaid the debt incurred by previous trips onto these very same waters. Enormous smiles, "high-fives," backslaps, fist bumps, hugs; all were exchanged all around. We got what we came for today.

At one point, we agreed that the baby humpback was "checking us out" by making eye contact. Was it? I do not know. I choose to believe that we connected--that the small one became a recognized individual in our eyes at that moment. It felt similar to when you make eye contact with a toddler in an airport and she just stares into your eyes, neither smiling nor frowning--just checking you out. When that happens to me I make a face and smile and try to connect. Sometimes I do, sometimes I don't but either way I know what happened. Here, it is different. I don't know--I just think so.

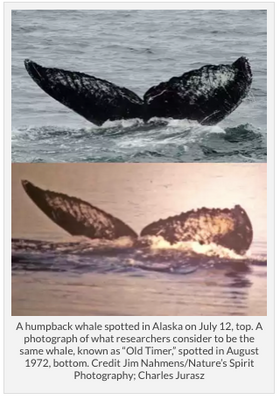

Once we humans identify individuals among the animals, give them names and follow their lives, it becomes more logical to consider them as being highly valued. So it is with "Old Timer." His ID goes back to 1972 making him the oldest known humpback whale in the world. His unique and distinctive fluke was spotted in Alaska's Frederick Sound just two months ago after having been unseen since 2015. Did someone like me see him as a calf 52 years ago? That is not likely. But we will never know, will we?

How do they figure this stuff out? Here is an excerpt from a New York Times article from three weeks ago:

The study is now entering the age of machine learning, with the help of an online platform called Happywhale, which collects whale fluke photos from scientists and members of the public from around the world. The Happywhale database currently contains roughly 1.1 million images of more than 100,000 individual humpbacks, said Ted Cheeseman, a co-founder of Happywhale and a Ph.D. candidate at Southern Cross University in Australia.

Artificial intelligence-powered photo matching algorithms help automatically identify the whales in submitted photos, aiding scientists in the field or others who need to look up previous sightings of a given animal. Want to participate? Go to happywhale.com and submit your photographs. Our friends at Whale Watch Cabo have submitted 2,405 photographs from 1,147 encounters making them last year's second most active participant in the program.

For these few days, we saw but seldom photographed whale flukes--the tails that beautifully rise out of the water and then power the whale downward. If they are intending to move forward, you do not see the tail, you see its humped back; you only see that tail when the humpback is heading down. For how long will that individual be gone? Maybe five minutes or maybe fifteen minutes. Where will it resurface to refill its lungs with air? Right over there or nowhere near. Remember that we divided our selves into a quadrant watch. One takes twelve to three, another three to six, another six to nine and another nine to twelve. When you sight a spout, you yell out "Eleven O'Clock, 100 Meters." Being the token American, I always estimated as "100 Yards" and it constantly confused my companions. To allow them to know me better, I began to estimate better: "Whale at seven o'clock, 82 yards." I got quizzical looks accompanied by gigantic smiles. This is fun, after all.

That is what makes this kind of experience so fulfilling. It isn't easy. It isn't guaranteed. It is unpredictable. It delivers failure after failure before granting success. So it has been these five days.