Chapter 14: Whales Going Forward?

The morning was interesting. Two fellow travelers were late for the bus and another did a training run 80% of the way from the hotel to Auke Bay—we picked her up at her 9.5 mile mark. When we arrived late at Hot Bite they were running late as well so nothing was lost. Two bald eagles were perched high atop a pine tree. I shot photo after photo and then went in for breakfast. Grayson was nowhere to be seen but he texted his mom that he was with a pair (the same pair I think) of eagles on the other side of the marina. I walked over there and had the most amazing encounter. For a while, I was six feet from one of these majestic creatures. It was scanning the water for food, ignoring me. Remember—I was six feet away, taking photographs. It was special.

But we came for whales.

A half hour out we encountered a group of six or seven doing what we came to see. Not as organized or as frenetic as the much larger group of two days ago, this bunch would first be astern, then on the port side, then starboard, then, well, who knew where they would surface. We photographers would spin our lenses in unison as Josh would call out, “on the left” or “behind us” abandoning nautical terms for simple directions. Sometimes we would get the shot, sometimes not.

A fishing boat was surrounded by this group at one point—Josh said he hoped the whales would not get tangled up in their lines. We do not want to experience an entanglement We stayed with them until noon and then set off to see if we could find orca.

Josh delivered. We found and then tagged along with a family of three. They would swim beside us, dive and be gone for several minutes and then reappear to entertain us once more. The baby loved to leap out of the water as it tailed its mother. The father swam further away only joining the other two on occasion. The water was joyously flat.

Then it was off to see if we could relocate our bubble net feeders from the morning. After a bit of looking, we found them. They weren’t netting. Their cruising was disorganized and more aimless than we had seen before.

But then, all hell broke loose. In front of RipTide, a jouvenile breeched. We all missed it. Then, it breeched a second time. We missed that too. The third time was the charm. I think every photographer on the boat captured that one.

Delighted with that success, we took a deep breath—but not for long. In rapid succession, three more breeches. Then, the icing on this cake: tail slaps. At least a half-dozen slaps in rapid succession and we all got photographs.

By that time, around 4:30, it was time to head home. Too many photographs? I apologize but this is like crack to a photographer.

One of the members of this last group had scrapes on top of its tail and a chunk taken out. Josh speculated—after having seen it earlier this season with an unblemished back end—that it had been attacked by an orca.

So, the danger here for humpbacks is natural—from orca—and manmade—from becoming entangled with fishing lines.

What is an entanglement? In the news just a couple of weeks ago, a humpback was spotted off the coast of Los Angeles with a rope trailing from its tail--something it swim through that became caught up in its flukes. Authorities lost track of that whale and it was believed that it did not survive.

Back in April, a NOAA entanglement team freed a young male humpback near Unalaska. Here's the description of how they did it from their website: "The team needed to gain access to the deep water lines wrapped around the animal's tail and connecting the whale to the anchoring gear. They used a new piece of equipment: a live-streaming camera attached to a 28-foot-long pole behind a knife. The camera enabled the response team to view the cutting action in near-real time. Like a surgeon's endoscope, this allowed the team to make strategic cuts remotely. The team was also making cuts to the rope on the outside of the body (i.e., an exoscope). "

Thanks to a "Slow Down School Zone" type California contest, some shipping companies are voluntarily slowing their vessels to minimize the chance that one of their vessels will hit and kill a whale. At ten knots or less, ships reduce whale strikes by 58 percent, according to NOAA, which sponsors this 'slow down' initiative. Even so, last year it was estimated that 80 humpback, blue and fin whales were killed in this fashion. The Benoiff Ocean Science Laboratory tracks this data through its "Whale Safe" program. The New York Times reported that the program's project scientist Rachel Rhodes said, "No one wants to hit a whale."

Here outside of Juneau, both Fingers and Ruffles are strike victims.

For the record, the Heritage Foundation, through Project 2025, "takes aim at NOAA saying it should “broken up and downsized” because “its current organization corrupts its useful functions.” Whale lovers and people who are interested in weather forecasts, etc., take note.

While in the waters around Juneau, these humpbacks must eat as much krill and small fish as they can find—as much as 3,000 pounds per day. They must create as much blubber as possible to sustain themselves for the winter in Cabo or Hawaii or wherever they migrate where there is very little for them to eat.

Down in the Baja, maximum humpback mating activity (this is a Smithsonian photo of that event) in the Baja occurs from late December until the end of January. How does it play out? Females engage in a “heat run.” As aggressive males begin to follow her, they compete physically to become the “Escort/pack leader.” That male is normally the one with whom the female successfully mates. After they tie the knot, the female begins her trek back to Alaska. Her gestation period is just shy of one year. She will return to give birth to her 1,200 pound, 12-foot-long calf in early January. The baby will eat only its mother’s milk and gains about 100 pounds a day.

The baby will remain with its mother for only one year.

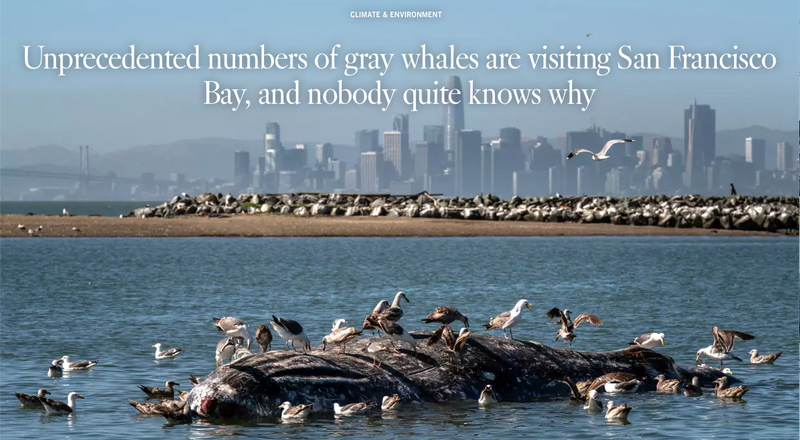

Almost three weeks ago, the Los Angeles Times reported that some of what may be these very humpbacks have been visiting San Francisco Bay along their migratory route from the Baja to Alaska. Consistently present off the coast, in 2016 “an influx of humpbacks” changed course to follow a “dense school of anchovies” into the bay resulting in a feast. Since then, the whales reportedly return annually.

At least one analyst ponders if that behavior is a sign that the whales usual feeding grounds are becoming less productive due to “extreme climatic changes taking place in the Arctic and the ocean.” Necropsy research on stranded whales which indicates that many were, in fact, malnourished.

Perhaps Dr. Meagan Jones' Whale Trust can help to figure some of this out. They conduct scientific research on the structure and function of humpback whale song across the North Pacific and their reproductive and mating behavior. The Whale Trust conducts community outreach events, educational field experiences such as this one, school outreach programs, mentorship and internships for students. If you want to help out, you can. They are a tax-exempt 501(c)(3), ein 91-2144632. Their budget is a small one--well under a million dollars--so anything you might want to send their way would be meaningful.

The United States "largely" made the hunting of whales illegal in 1971 and these whales remain protected under the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act. Way before that, in 1946, the International Whaling Commission was formed to prevent "overhunting" of whales. In 1982, the IWC called for a moratorium on all whaling with only Japan and Norway voting against it. In 1979, whaling-free sanctuaries were created in the Indian Ocean and the same was done for waters surrounding Antarctica in 1994. In my mind, saving the whales is one of the noblest of causes. There are so many urgent issues in the world today that these guys won’t make the top of most lists. That’s a shame in multiple ways.

Last month the New York Times reported that U.S. federal regulators at NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, gave approval to the Makah Tribe of Washington State permission to "harvest" up to 25 gray whales over the next decade. That right was granted based upon an 1885 treaty designed to, in part, preserve the tribe's way of life and culture. Fortunately, the population of Eastern North Pacific Gray Whales has rebounded from endangered to a population now estimated at around 20,000 individuals.

Still, for a whale guy, the idea of killing one of these creatures is troubling. I must empathize, however, with the Makahs. One wonders, however, what happens when other tribes or groups bring forth the same demand.

The Makah don't have a free hand. They must work out details, obtain a hunt permit, observe restrictions on when and how they can hunt and they have agreed that if the whale population falls, the approvals will be denied. In 1999, their whale hunt involved paddling in wood canoes for several days, harpooning a 30-foot whale, killing it with a high powered rifle and then towing it to shore where the meat was consumed in tribal ceremonies.