7/12 "An analog country in a digital age?" Let's find out.

I am asked: “Where in Europe should I go on vacation?” Italy or France? Maybe London or Athens? But Lisbon, Portugal? It's not the first place that comes to the American mind.

Perhaps that should change. Is history your thing? First settled in 2500 BC, Lisbon is eighteen centuries older than Rome. Are you a geography buff? Lisbon is closer to Casablanca in Africa than it is to Paris. Are you a foodie? Lisbon restaurants are making headlines. Hard to get to? Not at all; American Airlines flies us non-stop from Philadelphia but you can also fly non-stop from New York, Boston, Washington, Miami or Chicago on American, Delta or United.

But, no matter your wanderlust, it pales to that of the ancestors of today's Portuguese. In the 1440s, Lisbon’s shipbuilders invented the caravel, a compact vessel particularly adept at sailing into the wind. Using that ship design, for six centuries, they led the world in oceanic exploration and colonialization, creating what was arguably the first global empire in history.

In 1497, Vasco da Gama stumbled upon a natural harbor on the west coast of what is now India and called it bom bain, meaning, in sixteenth-century Portuguese, ‘good little bay.’ The Portuguese later gave the settlement to the English who anglicized its name, making it Bombay,’ which now, after independence, is Mumbai. Less than 400 miles south of Mumbai is Goa, a Portuguese colony until 1961 when the Indian army took it by force; 26 Portuguese soldiers died before the local commander surrendered. However, the Portuguese language still echoes there where, the New York Times reports, “Goans describe their own lifestyle as ‘susegad’ from the Portugese ‘sossegado,’ a term conveying the chilled-out contentment that comes from living there.”

And there is Brazil, now a nation of nearly 210 million people which was for three centuries a Portuguese colony after they arrived there in 1500.

Portugal, however, allowed itself to become vastly overextended and, unable to hold onto all it had amassed—and squandered—fell precipitously from its position of undeniable global leadership. It would not, after years of earthquakes, coups, little to no public education, assassinations and forty years of dictatorial rule by António de Oliveira Salazar, easily recover.

But much earlier, in 1791, Portugal was the tenth “country” in the world to recognize the young United States of America as an independent nation. (As a bow to the 243rd Independence Day just celebrated, know that, In order, the first to acknowledge our new nation were France, The Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Great Britain, The Principality of Brunswick-Luneburg (Germany), The Papal States, Prussia, Morocco and the “Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg.")

Around the same time, like the U.S., Portugal sadly and shamefully entered extensively into the slave trade, first kidnapping people from Africa’s west coast and later trading guns for slaves and taking them back to Europe. The country would only abolish slavery in 1869 when it entered into a treaty with the U.S. and Britain. Portugal’s Brazil wouldn’t follow until 1888. Equally shameful, Portugal has, during its history, driven out both Muslims and Jews but is known to have, under dictator Salazar, admitted several thousand Jewish refugees during World War II.

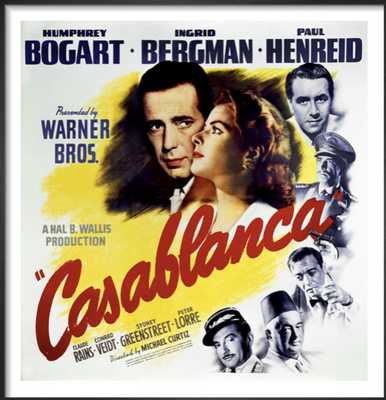

You may remember from the classic film, Casablanca, that one escape route from the rampaging Nazis was through Lisbon. Portugal (along with Sweden and Switzerland), said to be a strategy to avoid attack, was neutral during World War II. (Of course, so too was the U.S.—at least until December 8, 1941.) The classic film begins with this narration: “With the coming of the second world war, many eyes in imprisoned Europe turned hopefully—or desperately—toward the freedom of the Americas. Lisbon became the great embarkation point. But, not everybody could get to Lisbon directly. And so a tortuous, round-about refugee trail sprang up. Paris to Marseilles, across the Mediterranean to Oran [in Algeria], then by train or auto or foot across the rim of Africa to Casablanca in French Morocco. Here the fortunate ones, through money or influence or luck, might obtain exit visas and scurry to Lisbon, and from Lisbon to the New World. But the others wait in Casablanca, and wait...and wait...and wait.

As late as 1962, still under Salazar (the year the Beatles recorded their first record), quoting from Barry Hatton’s The Portuguese, A Modern History “in repressed Portugal, people still had to request a government license to own a cigarette lighter (to protect national match-makers), women needed their husbands’ written permission to open a bank account, and censorship was so tight that newspapers could not even criticize soccer referees because it amounted to questioning authority.”

My good and learned friend, Allan Katz, (shown in a 2013 Department of Defense photo below left with the U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, center, and Portuguese Foreign Minister Paulo Portas, right) was, in March 26, 2010, named by U.S. President Barack Obama to be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary for Portugal. He served in that capacity until July of 2013. (I was in Lisbon in December of 2011 for a couple of days but, sadly, I did not know His Excellency at the time and so neglected to call upon him.)

It is under the good graces of Ambassador Katz that B4 and I now join him and his lovely wife Nancy and two other fortunate couples (who like us had lobbied him to show them around) in our own exploration of Portugal.

When Katz recommended that, prior to our visit, I read the earlier quoted Barry Hatton book, I took his advice. Near the end of the book, Hatton writes about a national malaise that arrests Portugal’s progress. He says that a reluctance to change--accompanied by a suspicion of anyone with ambition and drive and vision--has dramatically held the country back. He says, “Portugal became an analog country in a digital age,” populated by those who “are not, on the whole, an especially ambitious people.”

Then Katz told me to watch the film: Night Train to Lisbon. Here's the plot: Raimund is a Latin teacher and an ancient languages expert. His life is transformed by a young woman on a bridge in the Swiss city of Bern, whom he saves from jumping to her death in the waters below. Raimund is intrigued but the woman disappears, leaving her coat. Inside it is a book by a Portuguese doctor which contains a train ticket. He uses it, setting off on a journey to Lisbon. While looking for the author, Raimund revisits a dark chapter in the country's history and unveils a tragic love triangle. He is drawn into a high-stakes puzzle.

Even with all of that background research, I found this to be the most extraordinary statistic of the many I discovered in preparation for this journey: “There are some five million Portuguese living abroad, roughly equivalent to half Portugal’s population.” Why does half a population leave home to live somewhere else? Remember, this is a home so fondly spoken of by my esteemed friend who got to know it and then, I think, fell in love with it.

Hatton’s book was written in 2011. Katz' experience began while the book was being edited. I am anxious to know what has happened in the most recent decade.

So this evening, to learn and find out, off we go on our Night Flight to Lisbon.